A note before reading this piece: We all navigate this world with our own experiences and own baggage, and we carry this baggage with us when we experience and interpret works of art. As a result, no text could be understood in the same way by two people, and different people are suited to different forms of explanation. In this piece, I have tried to explain concepts in a way that suits me, a student of the Classics (both Chinese and Western) and an avid fan of literature and the arts. I hope that my explanation can communicate the things I feel when I read classical Chinese poetry, but it most certainly will fall short in that regard. Nevertheless, I hope that through my attempts, some fraction of the beauty of these texts may be transmitted from the poets drinking and writing centuries ago, to you.

From Shakespeare’s “dish for a King” to Fitzgerald’s “finger-bowls of champagne”, alcohol and intoxication are concepts far from absent in the Western literary canon. Indeed, alcohol is a prominent feature in literature and art in every corner of the world, and the associated state of drunkenness a tool through which plots may be twisted and hidden emotions expressed. Although primarily considered a depressant, alcohol produced both stimulating and sedating effects in humans. Heightening highs and lowering lows, the substance sets the stage for deeply emotional episodes, makes and breaks relationships, and, unfortunately, enables addiction. Given its accentuating effect on human emotions, it is unsurprising that alcohol is both the beverage of choice for writers and artists seeking inspiration, and a mainstay in the creative products they produce. In turn, by examining the representation of drinks and drinking culture in literary works, one might be able to gain unique insights into the cultures and circumstances in which both author and story resides.

As Nicholas O. Warner writes in his introduction to the special, literature-focused issue of the Journal Contemporary Drug Problems, “cultural artifacts”, such as literary texts, may prove helpful to understanding “the values and beliefs underlying social behavior”, such as drinking. The ensuing articles in this issue discuss Finnish literature, American film, Irish drama, and Russian poetry, each explicating the nuanced connections between cultures and their literary products. Of particular interest is Julia Lee’s contribution “Alcohol in Chinese poems: references to flushing and drinking”, in which the author examines a claim arguing that the lower levels of alcohol consumption in contemporary China is a somewhat recent development. Indeed, after surveying many classical Chinese poems, it seems true that despite the population’s high alcohol sensitivity, consumption was rather liberal and less restrained during ancient times. Lee makes several interesting observations in her analysis, including how government censorship and prohibition may have warped literary depictions (literati-poets were often government officials, or at least aspiring ones), and how studying poems may reveal how much and for how long poets drank. Most notable, however, is her discussion of culturally-relative conceptualizations of drunkenness and the barriers to translation this erects. For example, Chinese character zuì (醉), most often translated directly as “drunk”, is believed by some sinologists to be a state less excessive than what the English word commonly denotes. Additionally, the character tuó (酡), describing the flushing reaction during drinking and in other situations, may have different connotations in China compared to the West due to the population’s physical sensitivities. Definitional and translation quarrels aside, it is clear, through both Lee’s study and the vast array of drinking related poems not encompassed by her survey, that many ancient Chinese writers enjoyed drinking and the feelings associated with the activity.

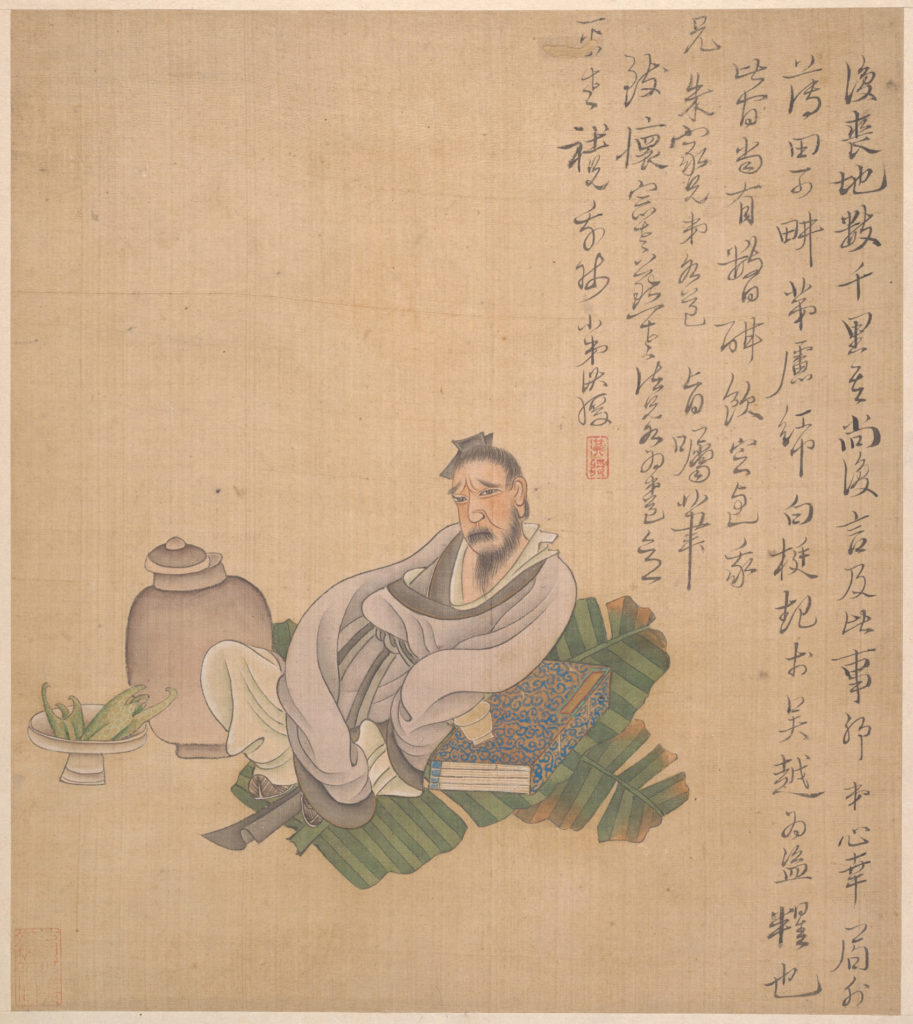

Despite this, the way in which Chinese poets drank and composed was markedly different from the anacreontic ways of many poets enshrined in the Western canon. In a letter to Maecenas, the Roman poet Horace references an ancient Greek edict which claims that no poetry of water-drinkers (contrasted with wine-drinkers) would please or be long-lived, listing many ancient Greco-Roman bards who drank liberally. Although the letter satirizes those unlearned men who try and gain poetic prowess through drinking alone, Horace does not deny that good poets do drink, and perhaps that drinking enhances their words. Indeed, the Greeks and Romans drank much wine, and often in social settings. At times, like during Symposia, the drinking was moderated, the drink itself diluted with water. At others, like during the notoriously debauched Bacchanalia, “when wine had inflamed their minds, and night and the mingling of males with females and young with old, had destroyed all sense of modesty, every variety of debauchery began to be practiced”. One would not, at least not explicitly, find descriptions of flautists performing sexual favors (they did during Symposia) in classical Chinese accounts of drinking. The fact that poetry, like all other literary forms, became closely bound to Confucian morality since at least the beginning of the common era, combined with the preservation of poetry being largely monopolized by governments, meant that classical Chinese poetry was a lot more subdued and conservative. Drinking was, for Chinese poets, not a license to participate in debauchery, but a channel through which noble ambitions and dignified emotions may be enhanced and expressed. Of course, drinking also served a social function, and when not drinking alone and lamenting personal circumstances, Chinese poets did drink with friends and female companions. Nevertheless, compared to the conceptualisation of drinking as the liberation from social responsibility and earthly concerns in the Western tradition, drinking in Chinese poetry harnessed, and only ever so slightly exaggerates the moments of inspiration that wine delivers to these upstanding gentlemen.

Indignation and unrealised ambitions

一壶浊酒喜相逢。古今多少事,都付笑谈中。

Meet and share a flask of murky wine, with cheer.

Then endless histories, past and present, may yield to our indulgence.

《临江仙·滚滚长江东逝水》明·杨慎 Yang Shen [Ming Dynasty]__

All translations provided in the body of my articles are my own. Although in the process of writing and translating I have consulted many previous (and better) translations. Some of the translations I consulted and my word-by-word annotations can be seen in our poems collection.

Despite the many formulae and conventions classical Chinese poetry adheres to, the identities of poets were relatively diverse. Since the establishment of a mature written tradition proper around 400 C.E., a vast array of poems by peasants, monks, courtesans, and imperial concubines have been recorded and preserved. Yet the typical writer of poetry in classical China is still undeniably a man of the literati class — one who may or may not have been of high birth, but nonetheless holds office in the bureaucracy after passing the imperial examination (kējǔ, 科举). In order to pass this examination, men often had to study the Confucian canon for much of their childhood and early adulthood, be capable of applying these canonical classics to current politics, and be skilled in prose-writing and versification. Advancing through the ranks of the Chinese cursus honōrum was difficult, both inherently, due to the rigor of the examination process and the demanding nature of subsequent appointments, and artificially, due to rampant corruption and political intrigue. Stagnant careers were, therefore, common for many literati-poets, and the associated indignation a prevailing theme in classical Chinese poetry.

The most notable example of a poet drinking away his indignation having suffered much in the supposedly meritocratic bureaucracy is Li Bai (李白) [701-762 C.E.], perhaps the most widely known classical Chinese poet both at home and abroad. One famous poem by Li, entitled ‘Bringing in the Wine’ (将进酒), is said to have been composed after the poet was dismissed from the imperial court at a whim, probably resulting from the machinations of political enemies. The poem, exhibiting a carpe diem attitude towards the perceived impermanence of life, is described by translator and scholar Stephen Owen as having “a frenzied intensity” and a “violent energy”, violates the usually restrained social drinking conventions. Rather than attempting to lessen his indignation by pledging Confucian self-improvement and expressing stoic disappointment towards corrupt politics, Li embraces an almost-anarchic attitude, implying drunkenness-induced elation and overconfidence as solutions to mortal concerns. Still, the most famous lines in the poem, given below, when decoupled from their poetic context, seem incredibly positive.

人生得意须尽欢,莫使金樽空对月。

天生我材必有用,千金散尽还复来。

A fulfilling life calls for limitless pleasures,

so let not the golden goblet rest empty beneath the moon.

My natural genius must be of use somehow,

so gold wasted in the thousands shall return again in time.

《将进酒》唐·李白 Li Bai [Tang Dynasty]

Yet when we consider the true motivation of this poetic persona — drinking to forget not only immediate personal struggles, but the universal struggles of all humanity for all eternity, the poem ceases to seem so light-hearted. One can feel the burning indignation and resultant escapism in lines like ‘I hope to fall into an abiding slumber, never returning to sobriety’ (但愿长醉不复醒), and ‘together with wine we will abate all eternal sorrows’ (与尔同销万古愁). For Li and many dejected literati-poets like him, being unable to fulfill their ambitions in serving the emperor, people, and country creates a gaping void in their consciousness, one that may only be filled by the intoxicating comfort of alcohol. Thus, Li invites his colloquotor, whom during the Táng dynasty may have been his drinking mates, now his readers a millenia later, to be enlightened about life’s transience futility, and then to drink with him. In drinking we may find truth, but we may also find solace.

For Li and many other great poets of imperial China, from indignation and unrealised ambitions spring often inspiration and unexpected genius…all it takes is a bit of wine.

Infatuation and unassuming desire

劝君莫作独醒人,烂醉花间应有数。

The only sober one you must not be, I urge,

For numbered are the days of gross intoxication, among blossoms.

《木兰花·燕鸿过后莺归去》宋·晏殊 Yan Shu [Song Dynasty]

Sex and love are often key elements in Western works involving alcohol, and with good reason — booze not only reduces inhibitions, increases emotionality, but also is commonly believed to have aphrodisiac effects. Although no accounts of erotic parties like those in Greco-Roman literature survive from ancient China, classical Chinese poetry is not short of innuendo and erotic imagery. In particular, the cí (词), or song lyric genre, due to its popularity in entertainment quarters and common association with feminine emotionality, has produced an abundance of works dedicated to romance and intimacy. Designed to be sung by courtesans entertaining guests, song lyric poetry often inhabits a female persona, or at least describes a female lover as the main object. Consequently, the emotions imbued in these lyrics often escape the Confucian metanarratives and moral obligations literati were bound by in the rest of their lives, allowing poets to embrace sentimental themes and expressions.

One acclaimed song lyric poet, Yan Jidao (晏几道) [1038-1110 C.E.] explicitly links his poems composed for and during drinking banquets to universal emotions and experiences:

“In [my lyrics] I not only gave an account of things I held dear, but also depicted those momentary sounds and sights over a cup of wine, and the things on the minds of those spending time with me.“

Yan Jidao, Translated by Robert Ashmore

Indeed, unlike the traditional forms of poetry popular before the Song dynasty, song lyrics are not usually assumed to be autobiographical. Lyrics composed by Yan perhaps arose from a moment of inspiration in a drunken state, or were motivated by stories told by his drinking mates. Nonetheless the emotions and images in his works were no less moving than poetry stemming strictly from personal experience.

流水便随春远,行云终与谁同。

酒醒长恨锦屏空。相寻梦里路,飞雨落花中。

Flowing tides follow the flight of spring,

Floating clouds will finally rest with whom?

When wine fades, the blank brocade screen stirs resentment.

Seeking her in dreams, on that road of fluttering rain and falling flowers.

《临江仙·斗草阶前初见》宋·晏几道 Yan Jidao [Song Dynasty]

These lines form the second half of a poem describing memories of a loved one, who is supposedly now lost, never to be found again except in the persona’s drunken dreams. The natural imagery of tides and clouds flowing towards an unknown and unseen destination is particularly poignant, as it illustrates the futility of chasing this lost lover — she is like these at once ephemeral and eternal elements of nature, always there, yet always out of reach. Even in dreams, where the persona may attempt to seek his lover, she is obscured by the beautiful yet melancholy images of rain and wilting flowers.

In this case, alcohol serves as a key that unlocks nostalgic memories and enables hope for the lovers meeting again. One can only imagine how moving this lyric might be when sung by a beautiful courtesan to a room full of drunken guests.

Conclusion

In the lines on drinking written by Li Bai, the poet channels his passions, compounded by alcohol, through emphatic philosophical statements that show readers what his completely liberated mind thinks about the world. Contrastingly, in the lines by Yan Jidao, no statements are made. The lines consist only of meticulously crafted images, and any alcohol-enhanced emotions are hidden carefully within, generating a bitter-sweet aftertaste that may linger for quite some time.

No matter if the poet and his poetic subjects are drinking to remember or drinking to forget, it is clear that the affective effects of alcohol are capable of reaching through time and space, intoxicating readers both past and present. After all, in the words of Li Bai, “only the names of drinkers are immortal”.

I loved your text, since English is not my language, I was able to understand your analysis. I also agree when at the beginning you clarify that two minds will not understand the same text the same way, it is good to allow the other to express themselves, so that we will have a more global vision of what is happening, a more “gestaltic” view and we will gain in understanding. Thank you very much for starting this site, and sorry my poor English.